Abstract

In recent years, the Chinese government has initiated assertive centralization efforts in its approach to environmental governance. However, the efficacy of these initiatives demonstrates marked variability across different sectors. While the central-local relational framework has traditionally been employed to elucidate these disparities, its explanatory power is showing signs of strain. This paper, through policy analysis and field interviews, investigates regulatory conflicts in land use for ecological and agricultural purposes within China. The findings highlight instances of overlapping jurisdictions and discordant policy objectives among agencies responsible for delineating ecological spaces and agricultural zones. While these conflicts seem to stem from the dynamics between the central and local governments, they more accurately reflect the inherent characteristics of fragmented authoritarianism. This paper aims to expand the theory of fragmented authoritarianism by incorporating the dimension of inter-departmental competition into environmental governance, moving beyond the traditional binary analysis framework of central-local relations. It seeks to understand and critique its limitations from a broader perspective, emphasizing the role of departmental competition within fragmented authoritarianism. By analyzing this internal mechanism, the paper reveals a more nuanced governance landscape, essentially replacing the traditional central-local paradigm with a model that situates departmental competition within the overall context of fragmented authoritarianism. We propose two models for delineating competition among governmental institutions: the bureaucratic model and the charisma model, thereby advancing and deepening the application of fragmented authoritarianism theory in China’s environmental governance. This provides new theoretical insights for understanding the current challenges and developments in China’s environmental governance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Influenced by the awareness of the environmental crisis that emerged in the developed Western world in the 1960s and 1970s (Mol, 2000; Rome, 2003), environmental governance in China started in the 1970s and has developed over a longer period of time since then. In contemporary China, people’s basic living needs are gradually being met, and higher-level needs such as a good living environment are being raised, and environmental governance has gained unprecedented importance in national politics. In 2018, the report of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China proposed to build an environmental governance system with the government as the leader, enterprises as the main body, social organizations, and public participation (Zhang et al., 2019), a viewpoint that clarifies that the government is the central role in China’s environmental governance. However, academic research on the state of environmental government governance in China and its influencing factors is still lacking to explain many problems in Chinese environmental governance. In this paper, we will take the problems that have emerged in the operation of China’s spatial use control in recent years as an example and focus on the model of government environmental governance.

As a public good, the ecological environment is non-exclusive, non-competitive and external, and in general, it is provided primarily by the government (Hawkins et al., 2016; Matzek et al., 2019). Research on environmental government governance in China has long revolved around the theoretical framework of central-local relations. The main thrust of this theory is that the central government sets the goals and tasks of environmental governance, while local governments are the actual implementers of environmental governance, the interests between the central and local governments can misalign, and the local governments sometimes choose to collude with the local enterprises. (Hu and Shi, 2021). As a result, local governments that lack restraint tend to relax environmental regulations in search of economic growth and increased revenues. This theoretical perspective divides the development of environmental governance in China into different stages of decentralization and centralization based on whether the dominant power is vested at the central or local level. This theory can effectively explain the strong environmental government governance centralization measures taken by the Chinese Communist Party leadership after the 18th National Congress, which apparently enhanced the intensity of environmental governance implementation and its actual effectiveness. However, since 2018, the effectiveness of China’s environmental governance in different areas still varies, and there are still a large number of problems in ecological protection involving territorial spatial planning. In this regard, the traditional decentralization or centralization perspective alone cannot explain all the problems in China’s environmental governance. The study in this paper is based on new issues that have emerged in the implementation of the territorial spatial plan in China since 2018, pointing out that there is a certain overlap of responsibilities and tasks between different departments and that competition between different government departments also affects the actual operation of environmental governance in China, which is a new perspective that needs to be analyzed in depth.

In summary, this study explores the causes of the problems that have arisen in the spatial use control of China’s land in recent years, in order to remedy the limitations of previous studies. This study covers the following main aspects: (1) why scholars have traditionally chosen the central-local relationship framework to explain the internal logic of environmental governance in the Chinese government and the limitations of this theoretical framework; (2) the degree of planning conflicts that have emerged in China’s territorial spatial planning as well as use control practices since 2018, leading to different ways of adjusting the ecological protection red line in each province and further causing regulatory dilemmas; (3) Transcending the central-local relationship model, this paper introduces the political concept of fragmented authoritarianism. While these dilemmas seem to originate from central-local relations on the surface, they more profoundly demonstrate the characteristics of fragmented political authoritarianism, namely horizontal competition and uneven power distribution among government departments. These findings necessitate a reevaluation of the conventional central-local relationship framework, underscoring the limitations of attributing issues solely to central-local dynamics. This paper transcends traditional analyses by introducing a nuanced model of environmental governance within the framework of fragmented authoritarianism. Herein, we expand upon the seminal work on fragmented authoritarianism by Kenneth Lieberthal and Michel Oksenberg, situating our analysis against the backdrop of internal competition among bureaucratic institutions—a key aspect of fragmented authoritarianism that remains underexplored in the existing literature on China’s environmental governance. By intertwining the central-local relational framework with the competition among departments within the bureaucratic system, our discussion under the lens of fragmented authoritarianism examines how inter-departmental competition influences the power structure of environmental governance.

Our contribution lies in merging the traditionally dichotomous central-local relations with an in-depth investigation of inter-departmental competition within the FA framework. By doing so, we have unveiled how this internal competition, driven by bureaucratic and charismatic leadership models, significantly impacts the formulation and implementation of environmental policies. Contrary to the integrated authoritarianism perspective, which mainly focuses on the cohesion of governance in China, our approach thoroughly examines the inherent competition and decentralized negotiation processes within the state apparatus. This reconceptualization not only challenges whether existing theoretical models are sufficient to fully explain the complexity of China’s environmental governance but also introduces a more nuanced analytical perspective to capture the intricate interplay of power, policy, and governance within China’s political landscape, thereby advancing the application of fragmented authoritarianism theory in the context of China’s environmental governance.

Theory of environmental governance in China based on central-local relations

The evolution of environmental governance in China

Environmental governance in China has its own characteristics, and the internal logic needs to be examined in the context of the evolution of environmental governance in China. (1) In the first stage 1973–1993: China’s environmental governance tended to be decentralized in this phase (Yang et al., 2014). In 1973, the environment protection leading group of the state council was established as a state-level environmental protection agency, and since then environmental capital construction has been included in the national budget. The central government’s focus was on vigorously developing the economy to improve social welfare, during this period, it delegated financial and most administrative powers to local governments (Vivian Zhan, 2009).In this period, except for public affairs that are fundamental to the country’s livelihood, such as national defence and resource-based enterprises, other public affairs were devolved to local governments, so that local governments received fiscal and tax incentives and political promotion incentives, and had room to choose and compete in their public affairs governance strategies (Nee, 1989). This phase gave local governments more power and capacity, resulting in poor implementation of some central policies at the local level, environmental policies being one of them (Li, 2020). In addition, local governments restricted environmental agencies by limiting their budgets, staffing, job promotions, working environment (Jahiel, 1997), and allocation of resources, making local environmental agencies less able to regulate. Local governments are committed to local economic growth and will give priority to economic development if environmental management hinders local economic development (Tang et al., 1997). The local government is the “inaction” phenomenon common in environmental governance. (2) In the second phase, from 1994 to 2012, China’s environmental governance model was one of centralization under decentralization, and the implementation of the tax-sharing reform in 1994 reversed the downward trend in the share of central government revenues in overall fiscal revenues, and increased the central government’s role in fiscal allocation (Li, 1997). It improved the central government’s ability to exercise macro-control in fiscal allocation, and investment in environmental protection increased during this period. In the course of the tax-sharing reform, local governments gradually became relatively independent economic entities. However, the high degree of political centralization has enabled the central government to have effective financial instruments and official selection systems to provide financial incentives and constraints to local governments (Tao et al., 2018). During the same period, starting in 1994, the central government focused on integrating various assessment methods to establish a comprehensive evaluation mechanism for party and government leadership teams and leaders. This evaluation mechanism was linked to the promotion system, incorporating two intrinsic power mechanisms within China’s cadre evaluation system: top-down control and local autonomy. Moreover, the cadre evaluation process involved more bargaining and negotiation than commonly assumed (Wang, 2013). In 2008, the State Environmental Protection Administration was upgraded to a ministerial-level unit, which further strengthened the authority of environmental regulation, making centralization under decentralization more obvious and increasing environmental incentives. (3) In the third phase, from 2012 to 2018, the trend of centralization of China’s environmental governance model was further strengthened (Brødsgaard et al., 2017). In 2012, the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) became a key point in China’s environmental governance journey. The conference raised the importance of ecological civilization, marking an unprecedented rise in the priority of environmental protection in national policy. From this point onwards, environmental protection and sustainable development became the core elements of China’s macro-governance, setting the tone for future environmental governance towards centralization, systematization, and rule of law. Since the 18th National Congress, the central government has shown greater determination and action in environmental protection, which is reflected in a series of concrete measures and reforms. Weak environmental supervision is a prominent issue in environmental governance. China has improved the ecological and environmental regulatory functions of departments through the environmental protection inspection system, party and government responsibility, and environmental protection interviews. The central environmental protection inspection system is a typical case, the central environmental protection inspection system from 2015 carried out a pilot, the central environmental protection system through the officials to pursue environmental responsibility, and the local government will be ecological and environmental protection work into the governance and construction, and thus enhance the grass-roots level of environmental awareness, to solve the grass-roots level of environmental governance, this system is an important shift in China’s environmental regulatory mechanism (Chen, 2019). Central environmental inspections underscore a strategic blend of decentralization and re-centralization, where the central government retains the capacity to intervene and guide local authorities toward improved environmental compliance and governance. As a regulated campaign, the central environmental inspections can create sustained compliance effects beyond the duration of its activities (Shen et al., 2023). In 2013, the central government introduced “hard tasks” for environmental protection, and in 2015, it launched the central environmental protection inspection system, both of which were aimed at strengthening supervision and incentives for the implementation of local environmental protection (Wei and Kang, 2023). With the implementation of the vertical management system for monitoring, supervision, and enforcement of environmental protection agencies below the provincial level after 2016, the central government’s intervention in local environmental governance has been strengthened, and the incentives and constraints on local environmental governance have been increased (Zhao and Percival, 2017). (4) In the fourth stage, after 2018, China’s environmental governance had shown a trend of recent realization. The problems of cross-functional, overlapping control and different standards between departments exist in the environmental protection sector continue to exist, in order to address these outstanding issues, institutional reform was carried out in 2018, with the formation of the Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), replacing the former Ministry of Land and Resources, the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the State Oceanic Administration and the State Forestry Administration, further optimizing the functional configuration, increasing the ecological and environmental protection in the overall work, integrate the ecological and environmental supervision functions of various departments, through the organizational design and institutional arrangements about the environmental protection inspection system, the environmental protection interview system and both Party and government officials take responsibility for environmental protection, and they both fulfill official duties and uphold clean governance, and establish a sound accountability system for ecological and environmental damage and resource and environmental auditing system (Chen, 2022). At the same time, the central government has strengthened its intervention and incentives for local environmental governance, on one hand, through the reform of vertical management of environmental protection agencies monitoring, supervision, and law enforcement to break the inappropriate intervention of municipal and county governments in environmental governance, on the other hand, highlight the performance of the ecological environment by weakening the economic indicators of ecological functional areas. From the perspective of the evolution of China’s environmental governance, China’s environmental governance has changed from a tendency to decentralization to a trend of centralization and then to re-centralization.

China’s environmental governance system: centralization or decentralization

Scholars have engaged in a heated debate about whether China’s environmental governance model is centralized or decentralized. Traditionally, the relationship between the central and local authorities has been influenced by economic disparities and political factors, such as the selection and promotion system for local officials. This has led to the devolution of power and the application of competitive governance in environmental protection. In the academic discourse on China’s environmental governance, prevailing views have long focused on the dynamics of the “central-local” relationship.

Zhao and Percival (2017), describe a highly decentralized environmental governance system (Zhao and Percival, 2017). as well as Ma, Li, and others (2009), point out the over-centralization in environmental governance, both highlight the contradictions within China’s environmental governance (Ma et al., 2009). In line with the views of Eaton and Kostka (2018), they emphasize the challenges faced by the central government in the execution of environmental policies, particularly the conflicts of interest with central state-owned enterprises. This interplay of interests between the central and local governments, as well as different departments, further complicates the landscape of environmental governance in China. It underscores the limitations of vertical environmental authoritarianism along the vertical axis in addressing issues related to cross-border pollution and resource depletion (Eaton and Kostka, 2018). While the central government occupies a dominant position in legislating and formulating environmental policies, in actual implementation, provincial governments often follow their own suitable paths to meet control targets in the context of power devolution. Although this analytical perspective has undoubtedly played a role in revealing various aspects of China’s governance structure, its explanatory power remains limited, especially when capturing the intricate interactions within the vast bureaucratic system of the nation.

Lieberthal’s theory of ‘fragmented authority’ provides a frame of reference for understanding this complexity (Lieberthal and Lampton, 2018), a view supported by Tsai (2006), who describes China’s policy-making process as long, discontinuous, and incremental’, which highlights the impact of fragmented power structures across different government departments and levels (Tsai, 2006). From an institutional perspective, the institutional structure of environmental governance in China is characterized by complex and fragmented power relations within a centralized framework.

Competition and incentives

In our detailed analysis, we observe a growing academic interest in how competition and incentive mechanisms influence environmental governance in China. As highlighted in Ran’s (2011) study, the implementation of environmental policies by local governments is not only influenced by central policies but is also driven by their incentive mechanisms. The combination of horizontal and vertical interactions can lead to diversity in implementation outcomes (Ran, 2017). Additionally, the practices of local governments in environmental governance are often influenced by the personal career plans of local officials. Shen (2022) suggests that local leaders, aiming for promotion, may prioritize policies differently over various periods, leading to fluctuations in the implementation of environmental policies. This phenomenon fundamentally challenges the traditional assumption that local behaviors are solely driven by divergences of interest between central and local governments (Shen, 2022).

Under the perspective of fragmented authoritarianism, scholars have noted that the fragmentation of power is the very source of inter-governmental competition and transactions, as observed in the studies by Brodsgard (2016) (Brødsgaard et al., 2017) and Kellee Tsai (2006) (Tsai, 2006). These transactions and competitions often arise not from a shared environmental goal but as a result of individual career or political objectives. The research by Kostka (2018) further reveals the dilemmas in implementing environmental policies under fragmented authoritarianism, highlighting the tension between centralized environmental goals and the actual implementation by local governments. This not only underscores the inequities in policy execution but also reflects the dispersion of power in environmental governance (Kostka and Goron, 2021). More specifically, Zhou’s (2008) study demonstrates how different levels of government form alliances on the issue of air pollution control, leading to a deviation from environmental governance objectives, thereby deepening our understanding of the dynamics of local implementation under the backdrop of fragmented authority (Zhou, 2008). Similarly, Li (2020) emphasizes the impact of local decentralization, fragmented governance authority, and economic growth incentives on the deviation in the implementation of environmental policies (Li, 2020). The introduction of competition and incentive perspectives allows for the complexity of China’s environmental governance to be explained beyond the central-local relationship framework.

Building upon existing research, we present a more comprehensive and in-depth critique of the “central-local” relationship framework, arguing that the structure of China’s environmental governance is far more complex than what is depicted by this simplistic framework. The diversity in behaviors of local governments is not solely driven by direct guidance or divergent interests within the “central-local” framework. In fact, the variety of behaviors exhibited by local governments in implementing environmental policies reveals a complex dynamic of power fragmentation, often overlooked in discussions of the “central-local” framework. This finding reinforces the applicative value of the theory of fragmented authoritarianism in contemporary studies of China’s environmental governance.

Within the framework of fragmented authoritarianism, the relationship between central and local governments is just one aspect of a multi-dimensional analysis. Crucially, we emphasize the necessity of horizontal competition between departments within the system. This inter-departmental competition involves not only the competition, transactions, and negotiations between different government departments and levels but also the personal motives and strategies of individual officials in the implementation of environmental policies.

By integrating the theory of fragmented authoritarianism and moving beyond the traditional “central-local” model, we gain insight into a more complex and dynamic political ecology of environmental governance. In this ecology, the relationship between central and local governments, inter-departmental competition, and the strategies and motives of bureaucratic individuals collectively shape and drive the formulation and implementation of environmental policies. Our study enriches the understanding of the complex current state of China’s environmental governance with a comprehensive, multi-dimensional perspective. Furthermore, it strengthens the applicative value of fragmented authoritarianism in contemporary studies of environmental governance in China, offering new ideas and methods to understand and address structural issues in China’s environmental governance.

Methods

The process of promoting spatial planning and land use control in China is mainly through the formulation and issuance of corresponding regulations and policy documents by various levels of government and relevant departments, which are then implemented in practice. Therefore, this study mainly adopts a policy analysis approach, focusing on various laws, regulations, and policy documents at all levels. This is supplemented by field research and individual interviews with the relevant government departments.

The specific research materials come from four aspects:

-

1.

Since 2018, six high-level policy documents related to territorial spatial planning and the “Three Lines and One List” issued by the central government have been of general guidance. Such as the Several Opinions on Establishing a Territorial Spatial Planning System and Supervising its Implementation and the Guiding Opinions on the Integrated Delineation and Implementation of Three Control Lines in Territorial Spatial Planning.

-

2.

Since 2019, there have been 36 provincial environmental legislations stipulating the spatial planning of the national territory and related contents of the “Three Lines and One List”, including specifically two provincial environmental legislations of provincial people’s congresses (Tianjin and Hebei) and 21 provincial NPC standing committees with 34 pieces of environmental legislation.

-

3.

Since 2019, 32 territorial spatial plans (public versions) issued by various provinces in China.

-

4.

Since 2019, 32 “Three Lines and One List” zoning control plans have been released by various provinces in China. This covers 32 provincial-level units (governments of provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the Central Government, as well as the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps) in China.

Based on policy analysis methodologies, combined with field interviews, this study delves into the power structure of environmental governance in China. The field research includes interviews with leaders from provincial Environmental Protection Bureaus and Natural Resources Bureaus. These interviews aim to reveal the respondents’ roles and influences in the formulation of the Territorial Space Planning and “Three Lines and One List” policy, as well as their strategies for advocating their department’s voice within the bureaucratic system. Through these interviews, we collected firsthand information about the policy formulation and implementation processes, offering a deeper understanding of the practical workings of environmental governance in China.

This study conducted six field interviews and surveys between October 2022 and March 2023 in two provinces in Eastern and Central China. All interviewees were engaged in natural resource planning policy in some capacity, such as having decision-making authority at the legal and policy execution levels. They had all worked in provincial department-level units for over five years, were familiar with the formulation process of national spatial planning and the “Three Lines and List” planning, and included positions such as the Director of the Regulations Department of the Provincial Ecological Environment Bureau and the Director of the Provincial Natural Resources Bureau. The number of interviewed provincial unit leaders was relatively small, due to the limited number of leaders with decision-making authority in the implementation of these plans, particularly at the provincial department level.

The research employed a combination of open-ended and semi-structured questions, focusing on the role of the respondents in the formulation of the Territorial Space Planning and “Three Lines and One List” policy. This included lobbying efforts by leaders within the bureaucratic structure to defend their department’s voice and how they exercised decision-making power in the planning process.

To encourage more candid discussions, the authors assured interviewees that their names and the specific names of their cities or counties would not appear in the text or any publications. All interviews were conducted anonymously, and any information that could identify specific individuals or locations was removed during the analysis process. Interviews typically lasted one to two hours. Specific interview questions and more detailed interview information will be provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Kick to the steel plate: problems exposed in China’s territorial spatial plan

The report at the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China pointed out that “China ’s ecological environment has improved fundamentally and the goal of building a beautiful country has been basically achieved” (Xu et al., 2021). As the scope of environmental governance in China has expanded from pollution prevention and control to include a wide range of areas including spatial governance and ecosystems, the framework of central-local relations cannot fully explain the emerging issues in China’s environmental governance due to the complexity of China’s environmental governance model (Kostka and Nahm, 2017). This paper proposes a new perspective to rethink the Chinese environmental governance model around the field of ecological spatial governance in China in recent years.

In the process of spatial planning and use control of land in China, there are two systems, the “Three Lines and One List” system led by the Ecological Environment Department since 2014 and the “ territorial spatial plan” led by the Natural Resources Department since 2018. The former is gradually developed from the ecological protection red line, which mainly focuses on ecological function maintenance, environmental quality control, and resource utilization restriction of the ecological environment (Xu et al., 2021), forms an ecological access list through ecological zoning control and setting to build a differentiated integrated ecological and environmental management system (Wang and Wang, 2019); the latter is through delineating the “three control lines” of permanent basic farmland, ecological protection red line and urban development boundary to distinguish the scientific layout of various types of production, ecological and living spaces and realize comprehensive territorial spatial planning. Both systems use the “ecological protection red line” as a policy tool to achieve the common goal of ecological protection. It should be noted that although the original purpose of establishing the “Three Lines and One List” and “territorial spatial planning” system was to unify the original scattered plans and realize the “unification of multiple plans”, there are still some conflicts between the two systems in operation. In the past, several departments in the Chinese government had the authority to formulate plans, which were often divided by sectoral characteristics, such as special master plans for land, environment, water resources, soil, and other aspects. Some particularly important resources are further broken down into utilization plans, annual use plans, and specific exploitable target quantities for each administrative region. Such planning by decentralized departments has led to the chaos of multiple departments identifying the same parcel of land as being under their jurisdiction, resulting in conflicts between plans and difficulties in verifying the true status of resource development and utilization. The 2018 institutional reform led by the Party Central Committee and the State Council established the MNR to change this situation, unifying the previous planning around various natural resource elements into territorial spatial planning. However, the “Three Lines and One List ”system led by the Ecological Environment Department still continues to operate. These two systems overlap in terms of spatial control objects but differ in terms of the positioning of the systems, the competent authorities, and the technical solutions for their delineation. In China’s practice, these conflicts are mainly reflected in the different positioning of permanent basic agricultural land between the “Three Lines and One List” and the “three zones and three lines” of the territorial spatial planning, as well as the inconsistency in the rules of articulation and adjustment of the ecological protection red line commonly applied in the two systems.

The positioning of permanent basic farmland varies from place to place

According to the 2018 national institutional reform, the MNR is responsible for the spatial planning and uses control of the national land, and the core of this system is the “three zones and three lines”, which divides the national land space into production space, living space, and ecological space, and its core means of implementation include the delineation of three control lines, namely the ecological protection red line, permanent basic agricultural land and urban development boundary, in which the permanent basic agricultural land control line is placed under strict controlFootnote 1. As an important “One Line” in the “Three Zones and Three Lines” of territorial spatial planning, permanent basic farmland is the core content of the territorial spatial planning, and its delineation is combined with the tasks of territorial spatial planning at different levels and the management authority of different levels of governments and is delineated from the bottom up. Governments at all levels place the control line of permanent basic farmland as the core control. Except for infrastructure and livelihood projects included in the spatial planning of the land, and projects that do not break the scale of permanent basic farmland already recorded in the basic farmland reserve area, any other non-agricultural construction projects shall not occupy permanent basic farmland, and the basic farmland reserve area shall be reported to MNR for the record after acceptance by the provincial government.

In the “Three Lines and One List” ecological environment zoning control led by the Ecological Environment Department, there are no unified and clear regulations on permanent basic farmland. In other words, at the central level, the Guidance on the Implementation of “Three Lines and One List” for Ecological Environment Zoning and Control issued by the MEE in 2021 does not provide for the positioning of permanent basic farmland (Chen, 2022). At the local level, the “Three Lines and One List” implementation plans issued by each provincial unit do not provide for the positioning of permanent basic farmland. At the local level, the positioning and control requirements of permanent basic farmland vary among the implementation plans issued by provincial units, mainly divided into the following five cases (Table 1).

The articulation rules of the ecological protection red line in various places are unclear

The ecological protection red line is the common foundation of the “Three Lines and One List” system and the territorial spatial planning system. The system was launched in 2014, during which the MEE issued several normative documents regulating the delineation of the ecological protection red line to guide the delineation of the ecological red line, and formed the corresponding results of the delineation of ecological protection red line. After the institutional reform of the State Council in 2018, the positioning of the ecological protection red line has changed, from a special ecological spatial control system exclusively to a supporting system in comprehensive territorial spatial planning (Liu et al., 2017), and the responsible department has changed to the MNR. Although there are two stages in the development of the ecological protection red line, its basic connotation is to achieve the purpose of ecological environmental protection with a rigid control line, and the conceptual term “ecological protection red line” is also used, so its basic scope of coverage is generally the same. However, under the two different systems, the ecological protection red lines between the past and present have different institutional positioning, competent departments, and technical solutions for their delineation, which inevitably require some adjustment, thus creating the problem of the interface between the ecological protection red line in the original “Three Lines and One List” and the ecological protection red line in the territorial spatial planning (Chen and Song, 2014).

The rules that provide guidelines for the interface between the “Three Lines and One List” system and the ecological protection red line in the territorial spatial planning system exist at both the central and local levels. Among them, it is worthwhile to pay more attention to the local level. The “Three Lines and One List” system is prepared and published by provincial governments, and the territorial spatial planning system is divided into five levels and three categories according to different planning levels, with the current focus on the preparation of territorial spatial planning at the provincial level and below. The conflicts and adjustments around the ecological protection red line in the process of developing the two systems are mainly at the provincial level, so the provincial government needs to provide specific operational specifications for the interface between the “Three Lines and One List” and the territorial spatial planning. At the central level, although there are no guidelines specifically for the interface of ecological protection red lines, relevant normative documents respect the fundamental status of territorial spatial planning and emphasize the need for the “Three Lines and One List” system to interface with territorial spatial planning zoning and use control requirementsFootnote 2. At the local level, the normative documents issued by the provincial governments do not follow the higher norms based on territorial spatial planning, but show different characteristics, mainly including three states: (1) Formulation of territorial spatial planning based on the “Three Lines and One List” system; (2) Adjusting the “Three Lines and One List” based on territorial spatial planning; (3) Lacking relevant norms. As can be seen in Table 2, the ecological protection red line has been included in the territorial spatial planning, and the central-level document specifies the fundamental position of territorial spatial planning, but most provinces still choose the Ecological Environment Department to lead the “Three Lines and One List” ecological environment zoning control scheme to adjust and update the ecological protection red line. Since there is no significant conflict of interest between the central government and the local government in this area, this situation cannot be explained under the traditional “central-local” framework of explaining environmental governance in China, and further research and explanation are needed.

Discussion: understanding environmental governance in China from the perspective of competition among government agencies

This paper argues that the perspective of competition among government agencies provides a more practical explanation than other theoretical frameworks in understanding the current problems in ecological spatial control in China. In the previous section, we showed a series of problems arising from the operation of the “Three Lines and One List” and the “Three Zones and Three Lines” of territorial spatial planning, which can be summarized as the implementation of the two systems by provinces does not follow the macro policy guidelines issued by the central government in this area, and the positioning of specific permanent basic farmland and ecological protection red line is inconsistently implemented and enforced in accordance with the rules of articulation and adjustment, i.e., adaptations are adopted according to the actual situation of the region. This section will first analyze why the traditional “central-local” theoretical framework fails to explain the emerging environmental governance issues, secondly, it will specify how competition among government agencies has led to problems in the delineation and adjustment of ecological protection red lines, finally, it will attempt to show a preliminary analytical framework for competition among government agencies.

The explanatory limits of central-local relations theory and the introduction of inter-agency competition in a fragmented authoritarian perspective

Under the “central-local” theoretical framework, the adjustment of the ecological protection red line by the provincial government can be simply attributed to the deviation of interests between the central and local governments, but this explanation is not supported by the facts of the subject of this study. That’s because, on the one hand, there is no opposition between central and local interests in the process of territorial spatial planning, the two tasks of environmental protection and arable land protection are national obligations and basic state policies stipulated in the Chinese constitution (Lagerlöf, 1997), which have been implemented through various laws and policies over time. Within this legal framework, the actions of provincial governments are more about adapting to and executing central policies rather than simply deviating from central interests. Furthermore, the scope of the ecological protection red line and the core indicators of arable land tenure in provincial spatial planning are subject to the control targets issued by the central government. Although each province takes different implementation paths, they are designed to serve the same goal of completing the control indicators (Habich, 2015). On the other hand, both the “Three Lines and One List” and the territorial spatial plan are announced by the provincial governments and the specific delineation is carried out by the constituent departments of the provincial governments, which does not involve the expression of interests of multiple levels of governments; the preparation and adjustment procedures of the plan led by the provincial governments means that the process does not involve the interests game of different levels of government in the previous environmental pollution prevention and campaign-style environmental governance in the past. It is evident that the interaction between central and local governments in resource management and policy implementation is not a simplistic relationship of compliance or divergence of interests, but rather a complex process of mutual influence and adjustment. Local governments demonstrate a certain level of autonomy and flexibility in implementing land policies (Cai et al., 2021), yet they are also subject to various constraints. Despite the central government setting control indicators, local governments face multiple constraints during the implementation phase (Habich-Sobiegalla, 2018). Local governments adopt different paths and strategies based on their own conditions and needs (Cai, 2016). Local interests and circumstances can even shape and influence the implementation of national policies at the local level, especially in regions with unique environmental or cultural characteristics (Yeh, 2005). Therefore, it is imperative to transcend the traditional “central-local” dichotomy and adopt an integrated perspective for analyzing the intricacies, flexibility, and constraints of the interactions between central and local governments, thereby dissecting the operational mechanisms of environmental governance in China.

This brings to the fore the significance of the concept of fragmented authoritarianism in this context. Fragmented authoritarianism extends beyond examining vertical governmental relations, such as the central-local interplay. It brings into sharper focus the horizontal competition and networks of negotiation within the government, particularly at equivalent levels of authority. (Brødsgaard et al., 2017) This theoretical framework exposes the internal dynamics where various governmental departments and agencies may engage in competition and negotiation, driven by diverse mandates and objectives. By employing the lens of fragmented authoritarianism, we gain a more refined and comprehensive understanding of the intricate web of lateral interactions among governmental entities in China’s environmental policy-making. This approach provides a crucial analytical tool to enhance our grasp of the complexities of environmental governance in China, illuminating the multifaceted nature of inter-agency collaboration and contention. Inter-agency competition is a well-established theoretical tool that argues that policy consensus is shaped by intense competition for goals and power among government departments. Differences in responsibilities lead different departments to see different aspects of policy problems and emphasize different solutions (Okhuysen and Bechky, 2009), and in this competition, power relations or policy influence among government departments will change constantly (Hartlapp et al., 2013). To clarify the powers and roles of different departments in China’s ecological spatial governance, it is necessary to briefly review the development of China’s ecological spatial control system with the “ecological protection red line” as the main line, focusing on the transfer of this task (or power) between different departments. (Brødsgaard et al., 2017) The “Ecological Protection Red Line” first appeared in Chinese policy texts in 2011Footnote 3. The development of this system has gone through three stages. Initially, the “ecological protection red line” was a comprehensive control system for the construction of ecological civilization, not only as a spatial boundary for strict control of things, but also as a management requirement in terms of quantity, proportion, or limit, with the MEE responsible for implementing the relevant control requirements (Yang et al., 2014). The second phase started in 2014 with the revision of the Environmental Protection Law, which included the ecological protection red line as a legal system and transformed from the initial comprehensive ecological civilization control system to a spatial control bottom line. The “Three Lines and One List” program was prepared and implemented by each province. The third phase started in 2018 with the institutional reform of the State Council, in which the newly established MNR was responsible for establishing a territory spatial planning system and for the unified management of all natural resources in the country, and the ecological protection red line was incorporated into the spatial planning system, becoming a supporting system for adjusting the ecological space among the three types of space: ecological, production and living.

From the above three stages of change, we can see that the task of delineating the ecological protection red line and related institutional construction has shifted from the MEE to the MNR, which is confirmed by the “Sanding scheme” that defines the powers and responsibilities of Chinese government departments. However, the Chinese government’s departmental structure still maintains the separation of resources and environment, while the MNR has been given the power to formulate national spatial plans including ecological space, the MEE still retains the responsibility of the ecological and environmental departments for monitoring ecological and environmental quality conditions and various nature reserves. If the reform is implemented along this line, the Ecological and Environmental Department will be reduced to an executive department in the management of ecological space, which will not only lose the achievements made in the process of formulating the “Three Lines and One List” in the past few years but also lose its leading power in the process of delineating and adjusting the ecological protection red line in the future, it will lead to the contraction of the power and discourse of the agency. Therefore, in the process of adjusting the ecological protection red line by the provincial government, the two stakeholder organizations, the provincial Natural Resources Department and the Ecological Environment Department, have gained a sufficient incentive to compete for the leadership of this task.

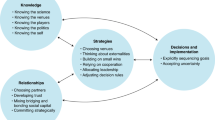

Explaining path choice problems in ecological space governance from the perspective of inter-institutional competition

In the process of competition among government departments, the reasons for determining the dominant authority are multiple. According to the bureaucracy theory, different government departments may have heterogeneous or inconsistent preferences and goals in the decision-making process due to different knowledge structures, functional scope, and service recipients (Allison and Halperin, 1972). Some government departments will use their advantageous resources to achieve authoritative “reproduction”, thus gaining higher decision-making influence. Asymmetric power and authority relations reflect the dynamic behavioral outcomes among government departments. It encompasses the ways in which government departments coordinate, persuade, bargain, and build alliances to achieve consensus on the goals or means of decision-making in different decision situations (Wu, 2020). In addition, the outcome of inter-agency competition can also depend on factors outside the operation of the hierarchy, such as the level of seniority and power of leaders between government departments at the same level.

In the research conducted for this paper, the head of the Department of Ecology and Environment in province S took the initiative to lobby the provincial government in order to preserve his department’s efforts in defining the ecological protection red line, emphasizing that the ecological and environmental department has expertise in the field of ecological protection red line, so the spatial planning of the province needs to respect the original work results and opinions of the Department of Ecology and Environment; while the head of the Department of Natural Resources in province H used to work in the Department of Ecology and Environment The head of the Department of Natural Resources in province H used to work in the Department of Ecology and Environment, so he strongly requested the Department of Ecology and Environment to adjust the ecological protection red line in the “Three Lines and One List” according to the results of the spatial planning after the spatial planning of the land led by the Department of Natural Resources was completed. The above two research cases correspond to the aforementioned inter-agency competition paradigm of hierarchy and individual will, respectively. The former is manifested in the evident competition among various government departments over resource allocation and setting policy priorities. Under the framework of fragmented authoritarianism, this competition involves not only the struggle for resources and influence but also reflects the efforts of different departments to exert influence in policy formulation to safeguard their interests. This inter-departmental competition, to some extent, fosters policy innovation and adaptability, but it also poses challenges to policy consistency and implementation efficiency. The latter is exemplified by the significant role of personal preferences and strategies of provincial unit leaders in policy formulation and execution. How they balance central directives with local practical needs significantly impacts the effectiveness of policy implementation. In the actual form of institutional competition, these two paradigms often exist in tandem, with each institution mobilizing multiple means to defend or expand its position to maintain its expertise and functional boundaries.

The interviews revealed that various departments involved in planning engage in competition, striving to expand their influence and obtain greater resource allocation during the process. This confirms the characteristic power struggles among departments within the framework of fragmented authoritarianism. Additionally, the preferences of individual leaders also impact the stance of departments in planning, reflecting the influence of personal leadership on policy formulation within this framework. A key feature of fragmented authoritarianism is that it encompasses elements of centralization while also displaying characteristics of decentralized power, which positions internal government departments and individual leaders as significant players in the policy process. Through preliminary testing in qualitative interviews, certain hypotheses and predictions of fragmented authoritarianism’s impact on the game of interests and individual influence in China’s governmental departments were validated, i.e., in a fragmented authoritarian environment, both individuals and departments exhibit significant competitive dynamics.

Inter-sectoral competition not only affects China’s environmental governance at the level of law and policy implementation but also profoundly influences the process of agenda-setting and political decision-making and is directly reflected in China’s notable tradition of “sectoral legislation”. The ability of government agencies to draft and submit draft laws on matters within their competence further anchors and reinforces their sectoral interests in the form of laws, a phenomenon that Chinese scholars refer to as the “legalization of sectoral interests” (Wang, 2016). Institutionalized authority profiles, such as the institutional reform program and the “Sanding scheme,” have not been effective in limiting the competitive dynamics between different government departments. Due to the lagging nature of national legislation, there is always room for specific inter-departmental consultations during each round of major institutional reform and policy deployment. In China’s recently introduced draft legislation, there are also contrasting claims about the priority subordination of the red line for arable land and ecological protection red line delineation in spatial planning, with different legislative and policy texts differing between ecological protection and food security values. In the aforementioned overarching policy platform for the territorial spatial planning system introduced by the central government in May 2019, it is required to “adhere to the priority of ecology and green development, respect the laws of nature, economy, society and urban and rural development, and carry out planning and preparation according to local conditions; adhere to the policy of giving priority to conservation, protection and natural restoration “. And in the draft Law on the Protection of Arable Land, submitted to the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress for consideration in September 2022, Article 7 stipulates that “the preparation of national land spatial planning should adhere to the priority of arable land protection, the protection of arable land and permanent basic farmland as an important element of planning, the overall layout of agriculture, ecology, towns and other functional space, the delineation and implementation of arable land and permanent basic farmland protection red line, the red line for ecological protection and urban development boundaries, the amount of arable land and the area of permanent basic farmland protection are clearly defined and made public in accordance with the law. The reason for this is that different departments dominate the formulation of draft legislation.” This provision emphasizes the priority of arable land protection in territorial spatial planning, but as analyzed earlier, its specific rules have not been unified in practice everywhere (Table 3).

Multiple factors affecting inter-governmental competition

This paper argues that by combining the traditionally dichotomous central-local relations with an in-depth study of inter-departmental competition within the framework of fragmented authoritarianism, we can gain a deeper understanding of the new challenges faced by China’s environmental governance in the transition from decentralization to centralization. In such a system, despite the centralized veneer of laws and policies, their execution may be rendered disparate and inconsistent due to inter-agency competition and overlapping functions. This view of internal institutional competition augments the traditional analysis of central-local relations, facilitating a more comprehensive exposition and understanding of the intricacies of China’s environmental governance. It underscores the potential for disjunctions and coordination challenges during the implementation by various governmental bodies. Hustedt & Danke distinguish between technical logic and political logic in the coordination of governmental inter-agency games (Hustedt and Danken, 2017), which correspond to technical and political behavior, respectively. The former focuses on professional judgment and information to achieve decisions in their own interest, while the latter uses power and interest exchange to achieve specific goals and interests. The division between these two types of games provides the logical basis for the different forms of inter-agency competition. From the previous analysis of Chinese eco-spatial governance practices, it can be identified that there are two types of inter-agency competition between government agencies, namely, section-based competition and individual will-driven competition, which follow two types of logic: technical and political, respectively. Inter-institutional competition in government relies on specific behavioral processes, in which the power relations or policy influence of the institutions will constantly change and ultimately affect the results of decision-making and the shape of law enforcement (Hartlapp et al., 2013). In the ecological spatial governance issue that is the focus of this paper, the game of inter-agency competition can be discussed separately at the central and local levels. (1) At the central level, the game based on the technical logic of the hierarchy is dominant, and the form of competition is mainly presented as seeking more resources for the sector by dominating law and policy-making. Take the MNR at the central level as an example, it is manifested in expanding the authority of this department and strengthening its unique knowledge information, and interests by drafting draft laws, and regulating and guiding lower-level governments to exclude the influence of other related departments in the implementation process as much as possible by issuing departmental regulations such as technical plans for the formulation of territorial spatial planning. (2) At the local level, the hierarchical game based on technical logic and the individual will game based on a political logic machine often exist together. Taking the research interviews of provincial Natural Resource Departments and Ecological Environment Departments in this paper as an example, in the decision-formation process of provincial governments, inter-institutional competition not only depends on the information, knowledge, and formal relationships within the section hierarchy held by the departments but also reflects the influence of the strong degree of different departmental leaders and social relationships on departmental power interactions, as well as the subjective will of local leaders on specific work The influence of the subjective will of local leaders on particular jobs. As a result of inter-institutional competition, ecological spatial governance in China has resulted in a situation where the same matter is dominated by different departments in different regions, and further influences the rules adopted in local legislation and local normative documents. Under the regime of fragmented authoritarianism, the formulation and implementation of environmental policy constitute a complex process involving multiple variables and multi-level dynamics. This complexity arises not only from technical and professional competition among departments but also from the influence of individual characteristics and political behaviors of leaders. Understanding how micro and macro factors intertwine in policy-making is crucial in this dual-influence model. If the above phenomenon is analyzed only from the perspective of central-local relations, i.e., the game between the upper and lower levels, it does not give a full picture of the motives, the game process, and the diversity of decision outcomes of provincial governments. Applying the perspective of fragmented authoritarianism facilitates a deeper analysis of the characteristics and effects of governance in China. However, it necessitates the development of an integrated analytical framework that incorporates multiple viewpoints and aligns with China’s realities. Within this framework, effective policy implementation largely depends on successful inter-departmental coordination and the individual capabilities of leaders. While the current trend of political re-centralization has led to a greater concentration of decision-making power in the central government, especially in the areas of environmental policy and major economic policies, this may have reduced the space for competition between local governments and different departments in terms of resource allocation and policy prioritization. This is because the central government, by strengthening its guidance and oversight roles, has more direct control over the actions of local governments and departments. However, during the implementation phase, the role of local governments remains crucial. Provincial governments and departmental leaders retain a degree of autonomy in actual execution, and the power struggles between departments continue. These internal dynamics may persist even as central authority is strengthened. The combination of inter-departmental competition and the personal rights of leaders forms a complex governance dynamic, influencing the formulation and implementation of environmental policies. By combining bureaucratic and charismatic leadership models, this analysis not only enriches the theoretical understanding of policy formulation and implementation under fragmented authoritarianism in China but also provides a structured framework for empirical research, aiding in the explanation and prediction of policy dynamics in similar political contexts (Table 4).

Conclusion

Focusing on the areas of territorial spatial planning and territorial spatial use control, this study reveals the impact of competition among government departments on environmental governance in China and advances the understanding of China’s environmental governance model from a new perspective. In the field of territorial spatial planning as well as use control, two major departments, the MEE, and the MNR, are closely related to the formulation, adjustment, and implementation of territorial spatial planning. Due to the lack of national legislation and uniform rules, different provinces have taken different actions in the delineation, adjustment, and regulatory measures of the red line for arable land protection as well as the red line for ecological protection. This poses two challenges: on the one hand, the different actions of different provinces will lead to differences in the level of natural ecological protection, which is not conducive to the effective promotion of ecological civilization. On the other hand, the traditional “central-local” theoretical framework cannot explain why there are significant differences in the rules of local governments regarding the delineation and adjustment of ecological protection red lines in the context of centralized environmental governance in China.

While studying the characteristics and mechanisms of China’s environmental governance, the “central-local” relationship framework has long been a dominant perspective. However, this framework can be overly simplistic and even misleading when explaining certain realities, as the actual situation is far more complex than this model suggests. Our paper proposes a detailed theoretical model grounded in the concept of “fragmented authoritarianism,” a distinctive feature of China’s administrative system. This concept allows us to penetrate the superficial “central-local” appearance, revealing an underlying network of political competition and negotiations, both vertically within hierarchies and horizontally across departments.

Despite strengthened central authority under Xi Jinping’s political leadership, the traits of fragmented authoritarianism persist due to various complex reasons. China’s vast bureaucratic system and extensive geographical distribution lead to a diffusion of power, and local governments maintain a degree of autonomy in implementing central policies, especially when addressing specific local issues and needs. While central consolidation might be emphasized during the policy formulation phase, local governments play a crucial role in the implementation phase. The power struggles between departments continue, and these internal dynamics may still be present despite increased centralization. We further observe a phenomenon of “integrated fragmentation,” where the central government, while strengthening centralization, attempts to more effectively coordinate and integrate the powers of different departments and local governments, indicating an adaptation and change in the form and operational mechanisms of fragmented authoritarianism, rather than its complete disappearance.

Any significant change in China’s political system during this period of transformation is gradual, and its effects and implications will take time to manifest. By adopting a more diversified understanding and reevaluating the over-reliance on the “central-local” narrative, the competition between departments reveals internal power dynamics and the complexity of policy formulation, while the central-local relationship uncovers the diversity and autonomy in policy implementation. The interaction of these two aspects forms the core of China’s environmental governance, enabling us to better decode the inherent structural complexity of environmental governance in China. Based on this, the paper proposes an integrated and diverse perspective, further delineating the competition within government institutions into models of bureaucratic internal competition and the dominant personal will of major leaders to understand the institutional competition and policy formulation process in China’s environmental governance. This perspective of internal institutional competition under the framework of fragmented authoritarianism complements the “decentralization-centralization” theory based on the central-local relationship, aiding in a more comprehensive identification of structural issues in China’s environmental governance, and providing insights for other countries undergoing rapid industrialization and urbanization.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Several Opinions of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China State Council on Establishing a Territorial Spatial Planning System and Supervising its Implementation, May 2019.

In 2021, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued the “Opinions on Deepening the Battle of Pollution Prevention and Control”; in 2021, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment issued the “Guidance on the Implementation of the “Three Lines and One List" Ecological Environment Zoning Control (Draft for Comments)”.

In 2011, the State Council clearly proposed in the Opinions on Strengthening Key Efforts of Environmental Protection (Guo Fa [2011] No. 35) to delineate ecological protection red lines to protect important ecological function areas, sensitive areas and vulnerable areas of land and marine environment.

References

Allison GT, Halperin MH (1972) Bureaucratic politics: a paradigm and some policy implications. World Polit 24(S1):40–79

Brødsgaard KE et al. (2017) Chinese politics as fragmented authoritarianism. Routledge New York, NY

Cai M (2016) Land for welfare in China. Land Use Policy 55:1–12

Cai M, Fan J, Ye C (2021) Government debt, land financing and distributive justice in China. Urban Stud 58(11):2329–2347

Chen H (2019) Institutional obstacles and governance paths of China’s environmental rule of law-based on the analysis of central environmental supervision science of law. J Northwest Univ Political Sci Law 37:149–159

Chen H, Song H (2014) The traceability and unfolding of the state’s obligation to protect the environment. Chin J Law 3:62–81

Chen R (2022) The evolution of environmental governance in China: process, characteristics and logic. J Chongqing Technol Bus Univ (Social Science Edition) 1–21

Eaton S, Kostka G (2018) What makes for good and bad neighbours? an emerging research agenda in the study of Chinese environmental politics. Environ Polit 27(5):782–803

Habich S (2015) Strategies of soft coercion in Chinese dam resettlement. Issues Stud 51(1):165-199

Habich-Sobiegalla S (2018) How do central control mechanisms impact local water governance in China? The case of Yunnan province. China Q 234:444–462

Hartlapp M, Metz J, Rauh C (2013) Linking agenda setting to coordination structures: bureaucratic politics inside the European Commission. J Eur Integr 35(4):425–441

Hawkins CV, Kwon SW, Bae J (2016) Balance between local economic development and environmental sustainability: a multi-level governance perspective. Int J Public Adm 39(11):803–811

Hu K, Shi D (2021) The impact of government-enterprise collusion on environmental pollution in China. J Environ Manag 292:112,744

Hustedt T, Danken T (2017) Institutional logics in inter-departmental coordination: why actors agree on a joint policy output. Public Adm 95(3):730–743

Jahiel AR (1997) The contradictory impact of reform on environmental protection in China. China Q 149:81–103

Kostka G, Goron C (2021) From targets to inspections: the issue of fairness in China’s environmental policy implementation. Environ Polit 30(4):513–537

Kostka G, Nahm J (2017) Central–local relations: recentralization and environmental governance in china. China Q 231:567–582

Lagerlöf J (1997) Lobbying, information, and private and social welfare. Eur J Polit Econ 13(3):615–637

Li J (2020) Environmental policy implementation deviation and its solution from the perspective of central-local relations. Dongyue Trib 41(04):53–59

Li Y (1997) Thinking about accelerating the construction of local financial resources. Explor Econ Issue (04):41–59 (1997)

Lieberthal KG, Lampton DM (2018) Bureaucracy, politics, and decision making in post-Mao China, vol 14. University of California Press

Liu X, Liu L, Peng Y (2017) Ecological zoning for regional sustainable development using an integrated modeling approach in the Bohai rim, China. Ecol Model 353:158–166

Ma H, Li B, Long J (2009) The theory of decentralization of environmental protection and practice. Local Financ Res 9:27–31

Matzek V, Wilson KA, Kragt M (2019) Mainstreaming of ecosystem services as a rationale for ecological restoration in Australia. Ecosyst Serv 35:79–86

Mol AP (2000) The environmental movement in an era of ecological modernisation. Geoforum 31(1):45–56

Nee V (1989) A theory of market transition: from redistribution to markets in state socialism. Am Sociol Rev 54:663–681

Okhuysen GA, Bechky BA (2009) 10 coordination in organizations: An integrative perspective. Acad Manag Ann 3(1):463–502

Ran R (2017) Perverse incentive structure and policy implementation gap in China’s local environmental politics. In: Local environmental politics in China. Routledge, pp. 15–37

Rome A (2003) “Give Earth a Chance”: the environmental movement and the sixties. J Am Hist 90(2):525–554

Shen SV (2022) The political regulation wave: a case of how local incentives systematically shape air quality in China. Cambridge University Press

Shen SV, Wang Q, Zhang B (2023) When fire alarm needs police patrol: Evidence from regulating firm-level pollutant emissions in China. Available at SSRN 4371501

Tang SY, Lo CH, Cheung KC (1997) Institutional constraints on environmental management in urban China: environmental impact assessment in Guangzhou and Shanghai. China Q 152:863–874

Tao L, Liu S, Liu H (2018) Does the spatial fiscal behavior exacerbate haze pollution? Based on the fiscal federalism-environmental federalism. Mod Financ Econ Financ Econ J Tianjin Univ 38:3–19

Tsai KS (2006) Adaptive informal institutions and endogenous institutional change in China. World Polit 59(1):116–141

Vivian Zhan J (2009) Decentralizing China: analysis of central strategies in China’s fiscal reforms. J Contemp China 18(60):445–462

Wang L (2016) Legislative bureaucratization: a new perspective for understanding China’s legislative process. China Law Rev (02):114–142

Wang Y, Wang Z (2019) The positioning and functions of the “three lines and one list” system and how to establish a long-term mechanism. Environ Prot 47(19):24–27

Wang Z (2013) Who gets promoted and why? understanding power and persuasion in China’s cadre evaluation system. In: Annual Meeting of the American Association for Chinese Studies, New Brunswick, New Jersey

Wei Q, Kang N (2023) Creating institutions to protect the environment: the role of chinese central environmental inspection. J Environ Policy Plan 25(4):386–399

Wu W (2020) A review of research on multi-sectoral decision coordination of government. J Public Adm 13(01):177–194

Xu C, Yang G, Wan R et al. (2021) Toward ecological function zoning and comparison to the ecological redline policy: a case study in the Poyang lake region, china. Environ Sci Pollut Res 28:1–14

Yang B, Gao J, Zou C (2014) The strategic significance of drawing the ecological protection red line. China Dev 14(1):1–4

Yeh ET (2005) Green governmentality and pastoralism in Western China: ‘converting pastures to grasslands’. Nomadic Peoples 9(1-2):9–30

Zhang G, Deng N, Mou H (2019) The impact of the policy and behavior of public participation on environmental governance performance: empirical analysis based on provincial panel data in China. Energy Policy 129:1347–1354

Zhao H, Percival R (2017) Comparative environmental federalism: Subsidiarity and central regulation in the United States and China. Transnatl Environ Law 6(3):531–549

Zhou X (2008) Collusion among local governments: the institutional logic of a government behavior. SociolStud 6:1–21

Acknowledgements

This research work has been funded by Major projects of the National Social Science Fund, China, grant number 22&ZD138.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HC designed the research and wrote the initial draft of this article, and writing—review of revised manuscript. LF made many constructive comments on the earlier versions. XS provided suggestions on the revised manuscript, as well as the editing work. All authors contributed to the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

No formal ethics approval was required in this particular case because (a) the data is completely anonymous with no personal information being collected; (b) the data is not considered to be sensitive or confidential in nature; (c) the issues being researched are not likely to upset or disturb participants; (d) vulnerable or dependent groups are not included; and (e) there is no risk of possible disclosures or reporting obligations. This study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, H., Feng, L. & Sun, X. Beyond central-local relations: the introduction of a new perspective on China’s environmental governance model. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 701 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03082-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03082-6