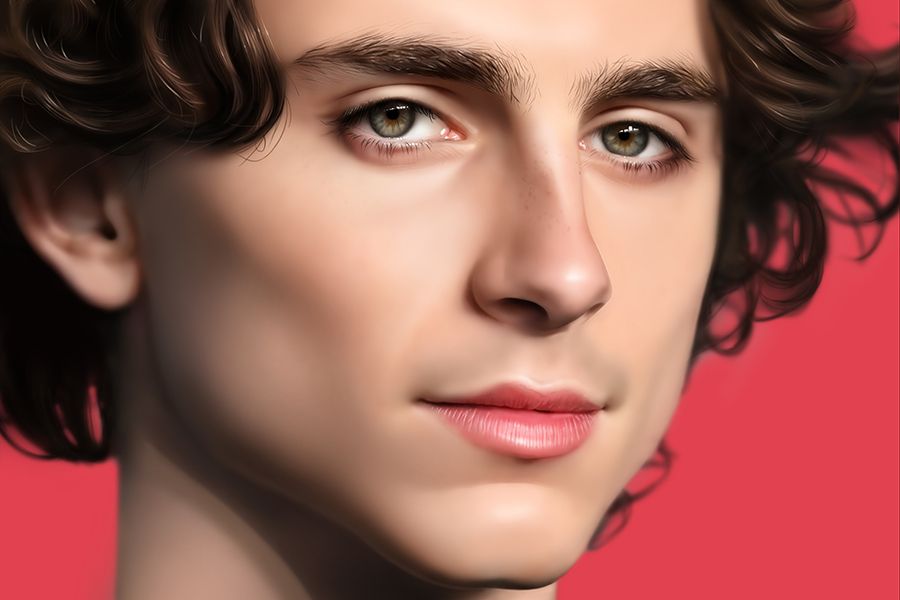

It was Miss Stevens that convinced me Timothée Chalamet was going to be a movie star. I’d seen him onscreen before — he had a recurring role in the second season of Homeland — but Julia Hart’s 2016 indie about a high-school drama competition was the first time I’d lingered through the credits to confirm his name. I had a feeling I’d be hearing it a lot.

He plays a kid named Billy, the most talented and most troubled of three students being chaperoned by the titular young teacher. At 19, Chalamet was able to put the childlike softness his face still had to great use, coming across as one of the adults or collapsing into boyishness. The movie withholds the sight of Billy performing until late, when he blows the roof off the auditorium with a monologue from Death of a Salesman. The material is comically mature for a teen, but when Chalamet directs his heavy-lidded gaze toward the camera, he doesn’t look like a kid playing dress-up. His conviction leaves you as worried about Billy as you are impressed by him — he’s not supposed to be able to relate to those themes of accrued disappointment so deeply. Not yet.

Movie stardom has always seemed to be a quality separate from acting talent. The latter can make you believe a performer could do anything. Stardom, though, is an alchemy of beauty and magnetism that convinces you that you’d be content to watch the performer do nothing at all. I was sure Chalamet had that elusive quality in spades, and a year later, he would certify it as the moody, precocious Elio in Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me by Your Name. His performance is inextricably youthful — a re-creation of the way a summer can stretch out forever and still feel too short. Seventeen-year-old Elio exudes an awareness of Armie Hammer’s 24-year-old Oliver from his every pore, so attuned to the older man that a casual hand on his shoulder is enough to stop him in his tracks. In the film’s famous last shot, Chalamet crouches, teary-eyed, by a fireplace, reflecting on first love as the credits roll. He holds the screen for three and half minutes, just himself and his character’s heartbreak.

Timmy Wéek

There’s Something About Timothée

The queer romance earned Chalamet an Oscar nomination and established him as cinema’s sensitive, simmering new prince. But no one can play the ingénue forever. Does Chalamet have what it takes to be a leading man five, ten, 20 years from now? Or, in a world where the film industry would rather invest in franchises than stars, is that even the right question to be asking?

Besides Guadagnino, the director who has most defined this era of Chalamet’s career may be Greta Gerwig. She has the best grasp on his mix of the dashing and the juvenile: In Lady Bird, their first collaboration, she cast him as Kyle Scheible, with whom Lady Bird (Saoirse Ronan) is immediately smitten. Kyle smokes and reads Howard Zinn and corrects Lady Bird’s pronunciation of his band’s French name — the callow heartthrob designed to be hilarious to adults in the audience while devastating the young women onscreen. (When Lady Bird finds out that he lied about the circumstances under which he relieved her of her virginity, he retorts, “Do you have any awareness about how many civilians we’ve killed since the invasion in Iraq started?”) Two years later, Gerwig cast Chalamet opposite Ronan again as Laurie in Little Women. He’s a very different character, the well-to-do boy next door whom Jo (Ronan) realizes destiny is conspiring for her to marry, though she won’t.

Chalamet is an ideal Gerwig ensemble player in that he has a gift for playing the kind of young men her protagonists will grow beyond. But he’s not the only actor capable of that. The monster hit Barbie, in which Ryan Gosling’s Ken feels like an oversize caricature of Laurie, hinted that

Chalamet may need Gerwig more than she needs him. Or maybe it’s just that if he’s looking for parts that demonstrate his chops as a leading man, he should not be waiting on a director whose focus is women. Could he take the route of another actor who debuted as a baby-faced heartthrob — say, lingering A-lister Leonardo DiCaprio?

Like Chalamet, DiCaprio started off on TV before staking out his serious-actor bona fides in films such as The Basketball Diaries. Like Chalamet’s, DiCaprio’s early fame was as much about his lissome beauty as his talent. Also like Chalamet’s, DiCaprio’s personal life has been scrutinized, beginning with the ’90s nightlife habits that earned him and his friends the “Pussy Posse” label. But there’s a lot about the older actor’s career that looks exotic in 2023.

DiCaprio has rarely had to choose between meaty roles and big paychecks. When he was young and felt his career was at an inflection point, he worried he would be seen only as a romantic lead after starring in Romeo + Juliet and Titanic, a concern that’s downright alien today. In 2000, he was able to take a high-profile gamble on Danny Boyle’s The Beach, a project that, if made this year, would be a niche FX-on-Hulu miniseries and not a fascinating misfire that nevertheless earned $144 million at the box office.

Two years after that, DiCaprio starred in Gangs of New York, his first film with Martin Scorsese, giving a feral performance that staked out territory for his future as a multifaceted leading man. Scorsese and DiCaprio have now made six films together, most of which have achieved an increasingly rare mix of awards attention and commercial success. The closest Chalamet has gotten to working with Scorsese has been starring in the director’s Chanel perfume commercial.

Nonetheless, Chalamet definitely seems to want to be a movie star in the DiCaprio vein. It has been a decade since he took a TV role. He has also, pointedly, yet to give in to the gravitational pull of superhero fare, which puts him ahead of the curve — strapping on the spandex now looks like a Faustian bargain in which an actor entangles their public identity with a masked character that could outlast or overshadow their own appeal. Tom Holland may make for an endearing Spider-Man, but when he made an Apple TV+ series, the movies’ audiences didn’t exactly flock to it.

As the lines of Chalamet’s face have become more defined, his cheeks hollowed and his jaw squared, what he most resembles is a rebellious aristocrat who may or may not step into the title he’s poised to inherit. This quality has informed so many of his roles; he even played a princeling back in those TV days as the coddled son of the vice-president on Homeland. Then there was the part of Nic Sheff in the film Beautiful Boy, which presented the addiction battles of a young man growing up in the all-organic comforts of Marin with the aestheticized reverence given to depictions of the death of St. Sebastian. In the forgettable Shakespeare-adjacent historical epic The King, he played the bratty Henry V, attempting to out-intensify co-star Robert Pattinson but being out-weirded by him instead.

The most prominent of these is his part in Denis Villeneuve’s Dune. It’s a blockbuster but a prestige one, and a franchise film but a strange one, based on Frank Herbert’s feverish space opera about galactic factions warring over a mind-altering, interstellar-travel-enabling narcotic. Chalamet is genuinely good as Paul Atreides, a space lord’s son who has been engineered to be a messiah but is deeply ambivalent about the prospect. Chalamet understands that the part is half-posing; two of the movie’s most enduring images are of the knife-handed salute he gives before a duel in the desert and of him wearing a futuristic trench coat as he takes one last walk along the beach on his home planet. But he brings an emotional realism to an otherworldly context, homing in on the small beats rather than emphasizing the character’s more swashbuckling aspects. Early in the film, he and Oscar Isaac, who plays his father, walk among the graves of the Atreides ancestors and discuss their doubts about leadership. Chalamet’s open, vulnerable expression as Paul’s father reassures him that he’ll always have his love sets up the weight of the loss he will later experience.

It’s easy to consider Chalamet’s potential but difficult to predict what he’ll be able to do with it. Even if Chalamet has the stuff, it’s useless without the buy-in of a blinkered and unadventurous industry, which has spent recent years strategizing to turn franchises, rather than stars, into the thing that lures people out to theaters. Celebrity persists, but movie stardom — the state of being someone people want to see on a big screen because that’s the only screen size that fits — seems more and more like a kingdom that’s closing off. There’s no better evidence of that than Wonka, in which Chalamet becomes the third actor to play chocolatier Willy Wonka onscreen. A musical prequel to Charlie and the Chocolate Factory isn’t an obvious next step for one of the industry’s anointed heirs, even though the director is Paul King of the universally beloved Paddington films. The trailers play strangely coy about Wonka being a musical, and it’s clear the studios feel lost, whether Chalamet knows what he’s doing or not.

Back in February, National Research Group conducted a survey about the actors people would come out to see in theaters, and the only performer under the age of 40 who ranked in the top 20 was the then-39-year-old Chris Hemsworth. Chalamet was way down at No. 94, a rank that feels less important than the fact that he was one of only four actors on the list under the age of 30. Hollywood has shown so little interest in cultivating movie stars that actors have taken the task up themselves — like Glen Powell, who has “It” and knows it and who basically staged his 2023 as a defense of the thesis that he should be the next great leading man. Chalamet seems far less certain of the kind of leading man he sees himself becoming, going from Wonka to a young Bob Dylan in James Mangold’s upcoming biopic. What he needs, more than anything, is his answer to Scorsese — a creative partnership with someone who sees him as more than a repository for untapped promise.

More from Timmy Wéek

- Timothée Chalamet Has Been Playing Great Bad Boyfriends Since Homeland

- We Néed Timmy’s É

- Whither Timothée Chalamet’s Bleu de Chanel Commercial?