Inside Ukraine’s Wartime Bar Scene

The country’s hospitality industry has lost talent to both the West and the front line. But as I found out at Kyiv's first bar show since the Russian invasion, it's still a hotbed of creativity.

I returned to Ukraine on the last Friday night in April with the promise of unseasonable warmth and sunshine, but as the train pulled into Kyiv, the overnight threat of a Russian missile attack loomed large. A Belarusian KGB chief had accused two Kyiv hospitals of housing Ukrainian soldiers, prompting their immediate evacuation. Air raid sirens sounded across the city prior to the mandatory midnight curfew, and as the streets cleared of traffic, only the sound of barking dogs and those wailing sirens could be heard until 4 am the next morning.

I hadn’t originally planned to travel to Kyiv that weekend, but when I saw Ana Reznik, a top Ukrainian bartender working in London, had posted about the first bar show held in the country since before the Russian invasion more than two years prior, I was inspired to join her. Spilnota, which is Ukrainian for “unity,” sought to bring together bartending talent from Lviv, Odesa, Dnipro, Vinnitsa, and Kyiv—and to serve as a homecoming for two women who had left the war-torn country to advance their careers abroad. No able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 60 are legally able to leave Ukraine, but Reznik, having found opportunity at A Bar with Shapes for a Name, and her friend Anna Moroka, who now works at Le Syndicat in Paris, were eager to return and together speak about what they had learned while working at two of the best bars in the world.

The weekend also presented me with an opportunity beyond the scheduled talks and tastings—the chance to experience the best of nightlife in Kyiv with Reznik and Moroka as my guides. It’s a more resilient city than it was in February 2022, when Ukrainian forces were on the defensive. A determined military campaign, bolstered by civilians who took up assault rifles and, at President Zelinskyy’s urging, made homemade Molotov cocktails from bottles on hand during a temporary nationwide ban on liquor sales, ensured the city remained under Ukrainian control throughout the worst of the initial six-week offensive. Now the city’s infrastructure is restored, international retailers have returned, and high speed rail travel is taking wary soldiers east and women and children west at all hours.

Despite the fact that tourists still have not returned, the hospitality industry was finally finding an equilibrium. Yes, they’d lost local talent to both the West and the fate of the front line, and were contending with the rising cost of spirits and stagnation in pay. (Not to mention the pressure on staffs to fundraise and on patrons to donate with each dropped check.) But as I’d soon find out, determined creatives were eager to evolve their craft despite being separated from their families, and industrious entrepreneurs were carving out fantastical party spaces hidden in plain sight.

Entering Ukraine was time-consuming, but mostly painless. I flew from New York to Krakow, then hired a car service to drive me to Lviv, the biggest city in the western part of the country. The ride was six hours for about $350—a bargain considering it’s about $100 less than an UberX from Manhattan to Atlantic City. After lunch, I made the next six-hour leg in my journey toward Kyiv—this time on a high-speed train—arriving just past 10:30 pm. As I stepped out of the Kyiv-Pasazhyrskyi railway station, I could see the manager at the door of the McDonald’s across the street turning away customers ahead of curfew, so I found a taxi to usher me to the Holiday Inn just as the first air raid sirens began.

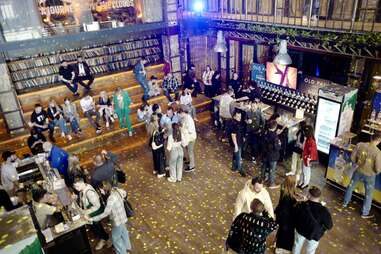

After two days of aggressive travel, I set out to stretch my legs and walk to the show, which occupied every floor of a bucolic coworking space on the Dnipro River, a 45-minute walk from my hotel to the far side of President Zelenskyy’s residence. The Holiday Inn was more modern and secure than my own Manhattan apartment building, and at $50 a night, it was also far more affordable. But I quickly realized I was on the wrong side of town. As I approached Mariyinsky Palace, I found the building was surrounded by a perimeter of anti-tank defenses and spiraling barbed wire that wove through the greenery of the neighboring park. Following a two-mile detour, I caught up with Reznik and Moroka upstairs at the Captain Morgan station, where a barman from Polunochnyky, in Vinnitsa, was showcasing his boozy interpretation of a beloved Ukrainian tea time snack.

Reznik unspooled her story over a round of the sweet-and-sour sippers topped with a square of buttered toast dolloped with homemade strawberry jam—nostalgia in a glass that usually goes for $6. The Donetsk native was forced to leave home in 2014 when the eastern region was first claimed by Russian separatists. She resettled in Kyiv, where she began her bartending career at a small speakeasy, then moved to Odesa in 2020 to work at top-rated Flacon, where guests select their drink by sampling different aromatics. One night in the early days of the invasion, her fiancé—a chef—was drafted. He was instructed to pack up his apartment and report for duty. As she counts down the next ten months of his deployment, Reznik is honing her craft at the Bauhaus east London mixology lab, which she said was an eye-opening experience.

“Ukraine was not touristy, even before the war, and the people judging cool bars are not in Kyiv or Odesa,” Reznik told me. She explained that, in Ukraine, successful bartenders often graduate to consulting or menu planning. In London, though, they work alongside newcomers, which inspires them to become better.

For her part, Moroka said the best bar crews operate as small families. But finding her new family took some effort. She left Ukraine a year into the war, once the Kyiv bar where she worked shuttered.

After first settling in Riga, Latvia, Moroka sought a warmer climate. “It came down to Spain or France,” she explained. “I didn’t speak either language at first, but I knew Paris had the better bar scene.” She arrived there in April and quickly found that the barrier to breaking into the scene went beyond language—no one had even heard of her last bar. It took fifteen applications to finally land a gig at Le Syndicat.

As Reznik, Moroka, and I moved across the floor to the Gordon’s Gin station, they introduced me to Vlad Baranov, the owner of Fakultat in Odesa. He mixed me a clarified chocolate milk punch with buckwheat butter-washed gin. While extolling the virtues of the local grain, he explained that he’d lost half his business and much of his team since the war began. “At the moment, they’re in Paris, Milan, Berlin, at 50 Best bars, and they have futures in the EU,” he said. “But I’m the owner of my bar, so my future is in Odesa, and I know Odesa will remain in Ukraine, so now I carry on by hiring like-minded people who share my vision.”

Baranov has maintained his bar’s pedigree in one of the most dangerous regions of the country, where most people are scared to travel. He recalled a time not long ago when Odesa saw 60 drone strikes in a single week, lamenting that unlike Kyiv, the city isn’t protected from attacks by missile systems, and air raid sirens offer minutes, rather than hours, of warning.

With no choice but to remain in the country, Baranov has been taking advantage of opportunity within. He told me he arrived to the city a few days early to bring Fakultat’s menu to industry favorite bar Beatnik for a night. “We sold out 450 drinks in two hours,” he said with pride.

That just happened to be where Reznik, Moroka, and I were headed next. Beatnik was originally a Kharkiv bar that relocated to Kyiv in 2019. A determined speakeasy with a counterculture spirit, Beatnik was one of the last great bars in Ukraine to be recognized by World’s 50 Best. It earned a spot on its 50 Best Discovery list in 2022, which was the last time any new bar in Ukraine received such recognition.

While its entrance was hidden behind an unmarked door on an otherwise quiet street, the room was already packed when we arrived at the start of Moroka’s 8 pm shift. An hour later, she’d sold out after pouring 100 Parisian concoctions mixed with ingredients like roasted coconut infused Calvados and Halva whiskey.

Last call in Kyiv exists in a gray zone between 10:30 and 11 pm, so we rushed to our next stop, Hram, which translates to “temple.” The bar opened last July, answering a demand for a more raucous party experience long absent from city streets where it’s become impossible to turn your head without seeing recruitment posters and wounded veterans. The venue promised a hedonistic escape and an open space for all faiths, nationalities, genders, and sexual orientations—all while constantly telegraphing its commitment to the war effort. When Reznik worked a guest shift in March, all the proceeds from the night benefited Future for Ukraine, a non-profit that outfits veterans with prosthetics.

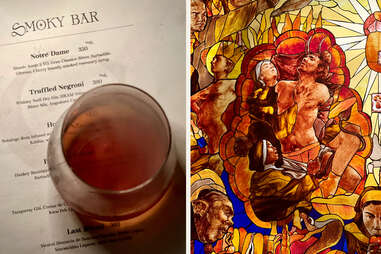

We descended into a sprawling split-level basement club cast in black and chrome and lit in hazy red lights. The aesthetic evoked multiple interpretations of the underworld, with revelers who looked as much at home in the John Wick cinematic universe as the afterlife. We slipped past a coat check that looked bigger than all of Beatnik, and settled for a drink at the first in a series of smaller tableaus each with its own unique energy. The Smoky Bar offered nothing but torched cocktails like a flambéed Notre Dame, and guests were also allowed to smoke. We had the perfect perch to breathe easy and survey the thumping chaos of the downstairs dance floor that upon closer inspection had its own order: A central bar slammed on all sides as barbacks restocked a tremulous tower of Champagne coupes stacked toward the ceiling mirror ball.

I held onto Reznik’s arm as we squeezed through the sweaty thump of the dancefloor toward a third bar marked by a towering stained glass window. Behind us, a gospel chorus in full choir dress, backed by a live band with a working organ that ran the length of the back wall, banged out disco pop and rap hits. Their rendition of “I Will Survive” worked the crowd into a frenzy.

We left before 11 pm—still too late for McDonald’s—but not too late to experience the charm of the city after dark. Partygoers paired off and descended into the underground crosswalks that link most corners of the city. The only places to congregate were in front of flower stalls, where subway horticulturists hawked fresh bouquets under halogen lights.

At the end of the week, Reznik, Moroka, and I found our way safely to the western border. I was the only man of fighting age in my train car as Polish agents collected our passports. And nearly every bag on board was opened and thoroughly searched for all sorts of contraband—including alcohol. Moroka had no problem bringing infused French spirits into Ukraine, but for now that cultural exchange remains a one-way street.