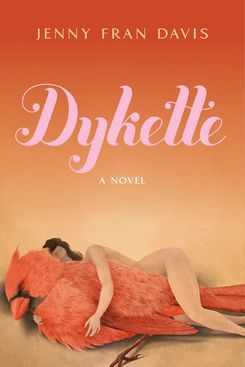

“It’s time to grow up. It’s time to be an adult, to be normal,” seethes Sasha, the titular “dykette” in Jenny Fran Davis’s queer zillennial comedy of manners. She says this shortly after her butch lesbian boyfriend, Jesse, declines to buy her an engagement ring. She’s half-serious, half-trying to be funny, as always.

It’s through Dykette’s Sasha, an insufferably needy high femme in her mid-20s (think Girls’ Hannah Horvath if she wore vintage pink nighties and was “straight for butches”) that Davis lays out her curiosity with queer domesticity. Sasha has the hots for Jules, a tall butch news anchor clearly inspired by Rachel Maddow, and both envies and pities Jules’s longtime partner, Miranda, for being old and boring, for having settled down in comfort and style. Though her own gaze might wander, Sasha comes totally undone whenever her boyfriend isn’t looking at her in a way that makes her feel truly seen — especially if Jesse is looking at someone else, like Darcy, his best friend’s girlfriend. Attention is Sasha’s lifeblood. If a butch isn’t looking at her, is she even there at all?

That’s what being a dykette means to Sasha: to be realized, made whole, by a butch’s gaze. “Seen by butch. Seen as femme,” Davis writes. “Maybe a better word for it was dykette. Containing both the butch’s gaze, and the femme’s stare. Because of course, they’re looking at each other.” Sasha romanticizes traditional marriage and suspects it may be the best way to secure Jesse’s undivided attention for good. She exalts domesticity, even fetishizes it, trying to out-housewife other femmes with her cooking and misguidedly thrifting a fur-trimmed wedding dress during a group shopping trip. But the fantasy of the traditional nuclear family ultimately fails to fulfill Sasha’s most desperate desires to be seen and therefore known and loved.

For a lot of queer people, especially those of us who experienced trauma in childhood, romance can feel like our best hope for love, stability, and safety. And when mainstream hetero culture glorifies marriage and the nuclear family, most of us tend to grow up believing that our parents, followed by our romantic partners, should be responsible for our emotional well being, our safety, our financial security — everything. But long-term monogamous partnership, no matter how loving and long-lasting, and no matter how much capitalism wants us reliant on the private family, can’t be expected to fulfill our every need.

Try telling that to Sasha. Dykette dangles perilously from the fine line between fetishizing normativity in subversive ways and merely reifying — or at least submitting to — an oppressive status quo. Performing gender as Sasha does, with her exhaustive lesbian processing, vintage head scarves and hunger to be worshipped as a pretty angel-baby bimbo princess, can be so much fun. It’s gender as bit, gender as farce, gender as pure pleasure. But it can also be exhausting and, perhaps, unsustainable long-term. Sasha, with Jesse, “never knew how much of the joy they experienced was material and how much was fantasy,” Davis writes. “That had always been the problem and would always be the problem.” Is there any greater fantasy than the expectation we should get our most fundamental human needs met by a single person?

Not that polyamory is necessarily the better option; I’ve learned the hard way that there’s just as much that can go wrong in an open relationship as in a monogamous one. Still, Sasha, Jesse, and their friends live in the same world the rest of us do, in which marrying your partner, joining households and having a kid or two are qualifications for being officially “grown up.” It’s the same world in which queer people are still figuring out how to celebrate growth and change without having to meet arbitrary milestones set by and for capitalist, heterosexist patriarchy.

—

In Dykette, Sasha and Jesse primarily fight about what he calls her “high femme camp antics.” Davis originally defined and described the term in a viral 2020 essay for The Los Angeles Review of Books, writing intimately about her own high femme camp antics, including “being cruel about other women’s looks if I was threatened by them” and a sex game called “Can I Come Inside?” involving a fantasy of violated boundaries, which she has written into the novel.

By the end of the book, I’d started to think of a “dykette” as the femme version of a “boi” or an androgynous masc/butch with Peter Pan syndrome. It’s common for queer people to experience a second, extended adolescence, having been denied an authentic queer youth or young adulthood. But who says we have to grow up by society’s oppressive standards?

Sasha playacts at adulthood when she tries to force her boyfriend to propose and commit to one day co-parenting children, before figuring out a little too late that that’s not the way she’ll get what she wants — if not that force isn’t exactly the best way to love someone. Petulant and self-absorbed, prone to public tantrums, she remains deeply immature throughout the novel, even childish. “Like poetry, she operated under dream logic — the logic of association, images, feelings,” Davis writes. Like poetry, I wondered— or like children?

Perhaps failing to grow up by the world’s limiting hetero standards only becomes a real problem when it prevents someone from working through their childhood wounds — because unless you put in real effort to process whatever might have gone wrong with your earliest human attachments, those pains can and will haunt your adult relationships.

I’ve dated lost bois who aren’t looking for a girlfriend or even a wife, but a mother figure to cook and clean and organize their lives for them while they fuck other people on the side. But shitty, immature behavior isn’t gender-exclusive. Enter the dykette. She is needy, irrational, hysterical, and mean, a toddler stomping around in her mother’s high heels. Both the boi and the dykette have a deep fear of abandonment and can strike out viciously when threatened. Both rely to an unhealthy degree on their partners to build and sustain their worlds. “You hold all of my reality,” Sasha tells Jesse during one of their many fights. “I rely on you completely to tell me how to think and how to feel. And you’re not taking that responsibility seriously at all.”

—

During a conversation about who will care for them when they all get old, Jesse remembers that the lesbian filmmaker Phoebe Livingston’s friends signed up in shifts to give her sponge baths when she was dying. “So you think you’ll have a band of young devotees to take care of you?” Jules asks. “What about when they have partners, though, and kids?” Miranda cuts in: “Being partnered doesn’t necessarily mean there’s someone to take care of you.”

There is radical potential in intergenerational lesbian friendship and community. But in Dykette, Sasha seems mostly uninterested in friendship, or at least in the kind of multigenerational queer community that Jules and Miranda might fold her into. These older lesbians aren’t real people to her but avatars to lust after and mock in equal measure. And for someone so obsessed with the working-class butch. and femme communities of the 1940s and ’50s, Sasha doesn’t give much thought to how those women’s lives could not look more different than her own in a post-marriage-equality world among the wealthy and culturally influential queers of modern-day New York City. The queers of Leslie Feinberg’s generation relied on one another to survive. Sasha relies on Jesse to give her identity — her life — its meaning.

A “dykette” is obsessed with aesthetics, symbols, and signifiers, and in Sasha’s case, this manifests in “looking the part” of the ultimate housewife as much as (if not more than) internalizing the ideals of one. But as enthusiastically as she plays her role, real life ultimately fails to match the fantasy. The little girl realizes she won’t ever be a real princess. Is that what it means to grow up? Sasha doesn’t get what she wants, but through her, Davis gives us honest if sometimes jumbled insights into a queer domestic fantasy stuck in a version of the past that has never really existed. Not that there’s anything wrong with a little fantasy. And maybe queer domesticity isn’t doomed — it’s just that a homonormative, assimilationist version of it is not enough to make us whole. It never has been.