This is part of Opinionpalooza, Slate’s coverage of the major decisions from the Supreme Court this June. Alongside Amicus, we kicked things off this year by explaining How Originalism Ate the Law. The best way to support our work is by joining Slate Plus. (If you are already a member, consider a donation or merch!)

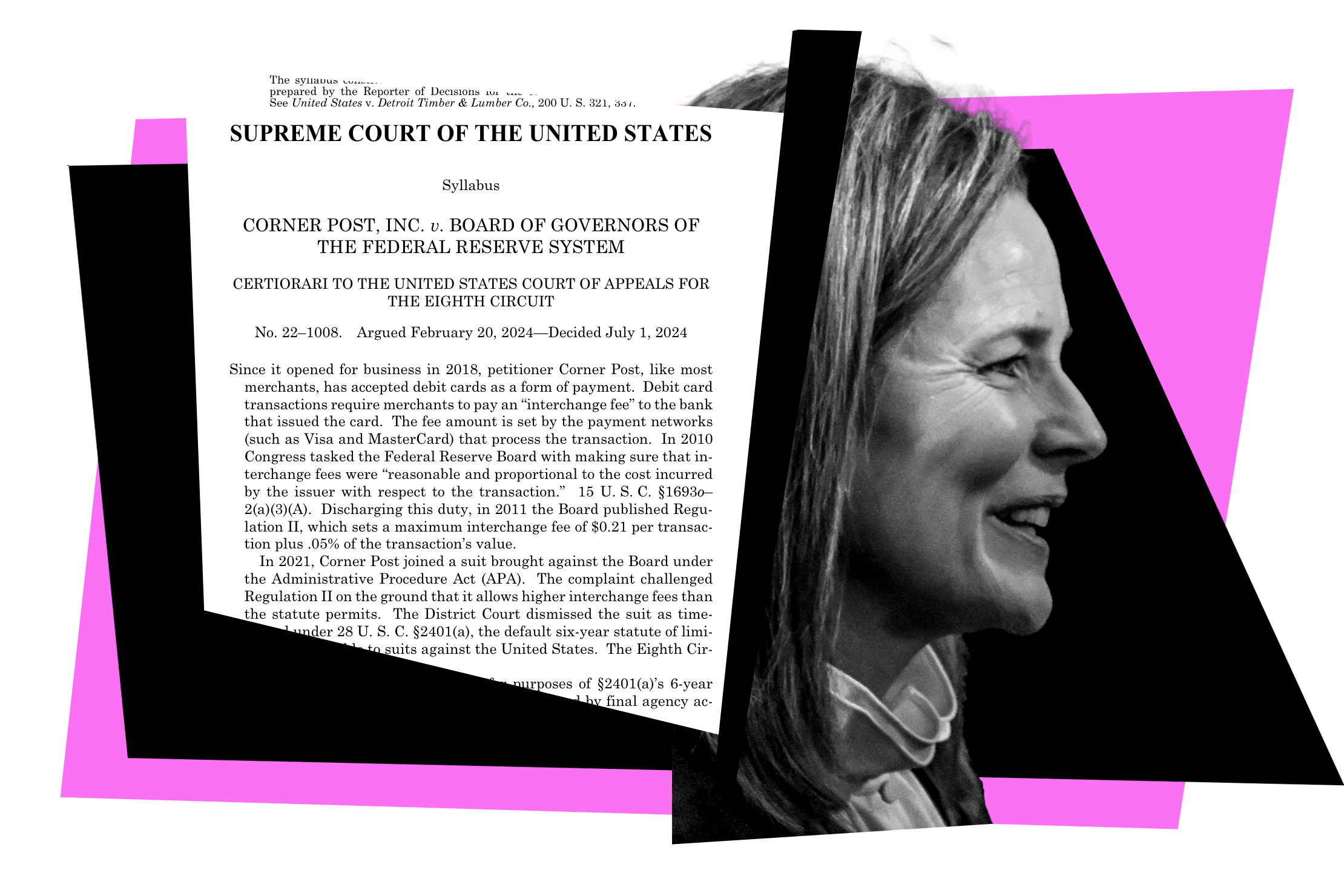

In the midst of a blizzard of Supreme Court decisions destabilizing the government as we have known it, many people might have missed a seemingly workaday case in which the court determined whether a lawsuit challenging a federal agency’s regulation was filed on time. In that case, Corner Post v. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the court held that the federal statute setting a six-year deadline for lawsuits against the government allowed a company to challenge a federal regulation long after it was enacted because the challenge came within six years of the date when the company—which was incorporated several years after the rule was issued—was first injured by the rule. In doing so, the court’s six-justice conservative supermajority disagreed with every federal appeals court that had squarely faced the same issue and opened the courthouse doors to challenges to long-standing, long-settled agency regulations.

Before Corner Post, the federal courts’ position on the required timing of a lawsuit challenging an agency rule was clear: Parties that wished to file a facial challenge—the kind of challenge that broadly questions the lawfulness of a rule as applied to anyone, not as applied to a specific person or entity in specific circumstances—had to do so within six years of the date the final rule was issued. This approach promoted legal stability by assuring agencies, Congress, regulated entities, and everyone else that a rule’s legal status would be cemented within six years after it became final. Now, after Corner Post, anyone with a brand-new grievance against a regulation can, no matter how long the regulation has been in effect, file a lawsuit to undo it.

To understand how disruptive the Supreme Court’s decision in Corner Post will be, consider another (seemingly unrelated) case from the court’s last term. In Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. FDA, an anti-abortion group and affiliated doctors challenged both the Food and Drug Administration’s original approval, issued in 2000, of mifepristone, a medicine used to induce abortions, and the agency’s more recent adjustments to the protocols for prescribing and administering the drug. Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk—a Texas-based federal trial court judge known for opposing both abortion and government regulation—held that the FDA’s original approval of mifepristone was unlawful and that removing the drug from the market was the right remedy. The federal appeals court in Texas rejected Kacsmaryk’s invalidation of the FDA’s original approval of mifepristone, not because it thought Kacsmaryk’s decision was wrong on the merits, but because the legal challenge to the approval hadn’t been filed within six years of the FDA’s final decision approving the drug.

Once anti-abortion litigants regroup and find a person or entity who, unlike the litigants in Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, has standing to sue, you can be sure that they will renew their challenge to the FDA’s original approval, a quarter of a century ago, of mifepristone. Corner Post will be there to speed them on their way. (This is probably no accident. The same law firm that represented Corner Post in the Supreme Court, Consovoy McCarthy, also represented anti-abortion groups in Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine. It would be naïve to suppose that the connection between Corner Post and mifepristone went unnoticed by one of the conservative legal movement’s go-to legal advocates.)

The potential for disruption caused by Corner Post is greatly magnified by the court’s decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, overruling Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council. Whereas Chevron had instructed courts to defer to agencies’ reasonable interpretations of ambiguous statutes, Loper Bright now forbids courts to defer to agencies and proclaims that every statute has one—and only one—best and permissible meaning, to be determined by judges, not administrators. There are thousands of long-standing agency rules that were upheld by courts based on the principle of deference embraced by Chevron. There are almost certainly also legions of long-standing rules whose statutory basis was not even challenged when those rules went into effect due to the strength and pervasiveness of Chevron deference. All of these rules are now vulnerable to lawsuits brought by newly aggrieved litigants thanks to the combination of Corner Post and Loper Bright.

The conservative justices’ attempts in these cases to wave away concerns about legal instability and mushrooming litigation against the government are risible. In Loper Bright, after eviscerating Chevron, Chief Justice John Roberts promised that the court was not questioning its prior cases upholding agencies’ decisions based on Chevron. It is strange that the lesser decisions, upholding one rule at a time, apparently deserve more precedential respect than the blockbuster case that dominated administrative law for 40 years. Even apart from that, it is hard to credit the court’s reassurance about stare decisis in the middle of a decision disrespecting stare decisis. And the court’s pinkie-swear promise about the continuing validity of its own cases relying on Chevron says nothing about what the lower courts will do with their own, far more voluminous precedent on Chevron. Will the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit—where federal regulations go to die—cling to its prior Chevron-based treatments of long-standing agency rules? Don’t hold your breath.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s reassurances in her majority opinion in Corner Post are equally hollow. She, too, thinks that stare decisis will largely take care of concerns about legal instability and judicial workload. New challenges to old rules will, she observes, often be resolved through binding precedent at the appeals court or Supreme Court level. This begs the question of how binding the courts will believe their precedent to be when it relies on Chevron. Moreover, since not all of the circuit courts hear every challenge to a rule, and since the Supreme Court only handles about 60 cases every year, well-funded litigants will almost always be able to find a congenial, and precedent-free, venue in which to press a challenge against a long-standing rule. In some federal courts in Texas, moreover, they’ll even be able to pick their judge.