With VB2019, the 29th Virus Bulletin Conference, a little more than three weeks away, we are excited that, with the addition of 12 out of 13 last-minute papers (the 13th will be announced on Thursday), the full

VB2019 programme has now been published.

In the last-minute talks, Kaspersky’s Brian Bartholomew will reveal details of the mysterious

SandCat actor, while HeungSoo Kang (LINE) will talk about targeted attacks against

cryptocurrency exchanges. Benoît Ancel (CSIS) returns to the VB stage to discuss the

Bagsu banker, while Thomas Thomasen and Loucif Kharouni (the latter also a returning speaker)

discuss how the Belt & Road initiative is a key driver for Chinese APT attacks. And, if you like topical talks, make sure you also attend that of Cisco researcher David Rodriguez and colleagues, who will

talk about politically targeted DNS surrounding the 2016 US Presidential elections, with an eye on the 2020 elections.

As in previous years, the conference features a number of Small Talks, which we previewed in a

blog post. This year’s Small Talks focus on retro-malware, domestic abuse and technology, burnouts, and cooperation between the security industry and law enforcement.

Tickets for the conference are still available, but with the conference only just over three weeks away, make sure you

register quickly!

Martijn Grooten

Editor, Virus Bulletin

For the privacy conscious among you: we do not track clicks on the links contained in this newsletter to individual subscribers, but should you feel more comfortable, we believe that any of the links mentioned here can be found through search engines.

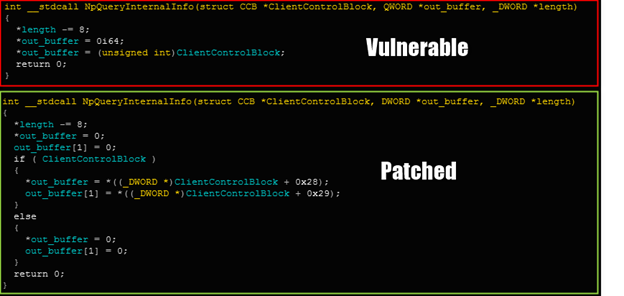

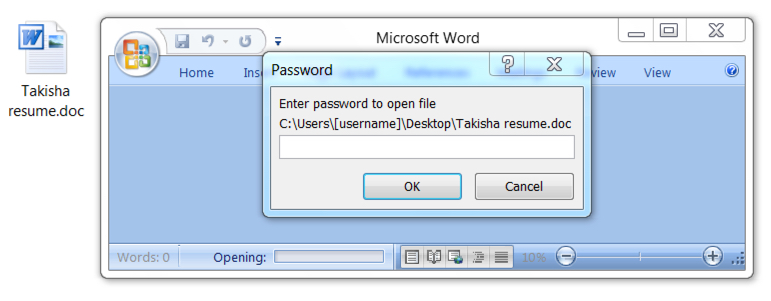

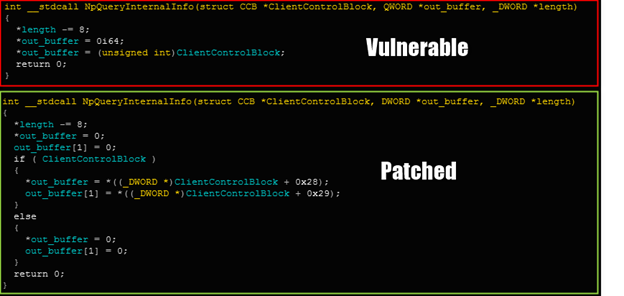

In one of the most notable discoveries of the year, in May Symantec

found that the Chinese

Buckeye APT group (also known as APT3) had been using some of the NSA tools prior to their being leaked by the Shadow Brokers. Check Point researchers Mark Lechtik and Nadav Grossman have performed an analysis of this group’s Bemstour exploitation toolset and

looked at how it is different from the NSA tools that were later leaked, providing some insight into Buckeye’s visibility of the original tools’ usage. In particular, they consider it likely that the group gained this visibility via a Chinese server targeted by the NSA.

After last week’s

report by Google’s Project Zero on five iPhone exploit chains being used in

watering hole attacks against what later became clear was the

Uyghur diaspora, Volexity has

details of websites that targeted the same community with exploits against Android and Windows. The company, which says that at least two Chinese APT groups are behind these attacks, has found circumstantial evidence that links them to the iPhone attacks. It is interesting to note that the 11 websites Volexity mentions match Apple’s “fewer than a dozen websites” in its much-criticised

response to the iPhone attacks.

ANSSI, the French national cybersecurity agency, has published a short report (

pdf) on “clusters of malicious activity” consisting of domain names and email addresses linked to

credential-stealing activity targeting government bodies and think tanks. Though ANSSI stays clear of attribution, it links the activities to those described in a number of other reports, including a recent Anomali

blog post, all of which were linked to

North Korea.

Proofpoint

reports updates to

PsiXBot, the .NET malware that has been quite prevalent since the beginning of the year. It is once again spreading through the Spelevo exploit kit, while it now uses Google’s DNS-over-HTTPS servers to obtain the IP addresses of the command-and-control servers. The researchers also found a sextortion module that looks for open windows with titles containing certain keywords indicative of the viewing of adult content, and which then records the activity of these windows, likely for extortion purposes. Worryingly, this could add credibility to the many sextortion scams out there.

Social engineering toolkits are closely linked to exploit kits but rather than target vulnerable browsers, they use social engineering tricks to lure users into executing malicious payloads manually. Malwarebytes’ Jérôme Segura

discovered the new ‘

Domen’ kit, which can display a variety of fake update alerts in no fewer than 30 languages.

Trend Micro’s Augusto Remillano II has

looked at a

spam campaign that uses hacked servers, accessed through brute-forcing weak passwords, to send spam via a PHP script, with the spam messages containing links to fake news stories on cryptocurrencies. The fact that such servers are better connected than home PCs, and that their IP addresses are far less likely to be blocked proactively, makes them ideal for sending spam.

In March last year, ESET

reported that the

Glupteba malware, previously linked to Operation Windigo, was being installed on its own through a pay-per-install scheme. Now, Trend Micro researchers Jaromir Horejsi and Joseph C. Chen have

found that the Glupteba dropper also installs a router exploiter and a browser stealer, while Glupteba has the interesting property of being able to obtain the C&C domain from the Bitcoin blockchain.

CSIS researcher Aleksejs Kuprins, who last year spoke at VB2018, has

analysed Joker, Android malware found in 24 apps in Google Play, with a total of almost half a million downloads. The malware downloads a second-stage payload which subscribes to premium rate services, clicks on advertisements and steals data from the device.

FunkyBot is another new Android malware that has been

analysed by Fortinet’s Dario Durando and that targets users in Japan. It has thus far limited information-stealing capabilities but appears still to be under development. Dario believes its authors are also behind

FakeSpy, Android malware that has been targeting Japanese and Korean users since 2017.

JSWorm is neither a worm nor written in JavaScript. The fourth version of this ransomware targeting Windows, which is notable through its adding of multiple extensions to the names of encrypted files, has been

analysed by researchers at Yoroi.

Not all ransomware targets Windows machines, though. Bleeping Computer

writes about the

Lilocked ransomware (called Lilu by its developers) that targets web servers and likely uses exploits to gain access to them. Not a lot is known about this malware, but the fact that search engines are indexing the encrypted sites proves that the malware is spreading in the wild.

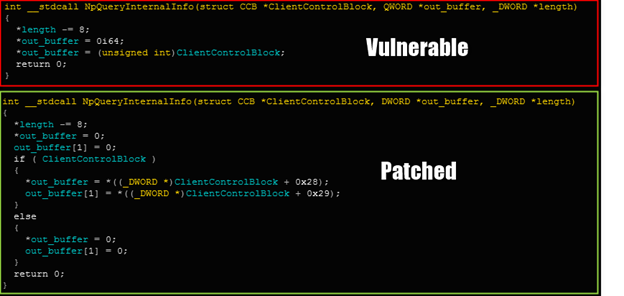

Two posts on the SANS Internet Storm Center blog look at recent

malicious spam campaigns: Jan Kopriva

analysed an email attachment with a large LNK file inside a zip archive that led to

Trickbot, while Brad Duncan

found password-protected Word documents claiming to be resumes that led to the

Remcos RAT.

In an interesting twist on the naming of malware, the authors of the ransomware

dubbed ‘

DoppelPaymer’ by Crowdstrike in July of this year are now using that name too,

according to BleepingComputer’s Lawrence Abrams.

The European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights and three other organisations have

filed a criminal complaint against three German companies for selling the

FinSpy/

FinFisher malware to the Turkish authorities. At VB2017, ESET researcher Filip Kafka gave a

presentation on FinFisher’s activities. Its targeting of users in Turkey was

reported by Access Now in 2018.

Finally, Kim Zetter has worked with Dutch journalist Huib Modderkolk to

uncover a missing link in the

Stuxnet story: that of a mole from Dutch intelligence who played a crucial role in the initial infections of the Natanz nuclear plant. An interesting fact,

reported only in Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant, is that members of the AIVD (the Dutch intelligence agency) sometimes receive a copy of Kim’s 'Countdown To Zero Day' as a parting gift. That book, which I

reviewed for Virus Bulletin in 2014, remains my favourite book on the topic of cybersecurity.

© 2019 Virus Bulletin Limited

The Pentagon, Abingdon Science Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 3YP, UK